The public is angry. For years, from coast to coast, waves of revelations about police misconduct have swept the nation. Treyvon Martin, Ferguson, police militarization, racist text messages. These names, words, and phrases have become household shorthand for police corruption on a continental scale.

And when we thought we’d heard it all, along comes the Oakland Police Department. If you’ve not read the recent revelations you may struggle to believe the story: OPD officers cover up a colleague who allegedly murdered his own wife, that colleague is then joined by over a dozen other officers in having sex with the young daughter of a police dispatcher. Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf, unable to find sufficient words, aimed her anger at the OPD’s “toxic, macho culture”.

As Mayor Schaaf did, it’s intuitive to blame police misconduct on the characters of particular officers. But what if the problem with the police is not merely bad people?

What’s going on here? …

This is the Oakland Police Department’s headquarters, a dystopic place if there ever was one. If this scary building could talk, what would it say? Perhaps…

“We [the OPD] are all-powerful”

“We are not a part of the community”

“Stay away”

Imagine working at this building day in, day out. No neighbors stop in to say hello, nobody passes by when you’re at your desk, there’s no casual interactions with members of the public. You and your fellow officers are holed up in this fortress-like environment. Over time institutional rot sets in, your isolation from the community turns into machismo and corruption.

If you wanted to isolate and corrupt uniformed officers wouldn’t you design a building like the OPD headquarters? Of course you would.

The same phenomenon can be seen with police forces around the nation: They are holed up in fortresses.

An armored vehicle full of prozac isn’t going to make anyone feel happy around these buildings.

Thank heavens, then, that there’s a silver lining to this dismal picture, a way to ease police corruption and isolation from the community. And that silver lining comes from Japan.

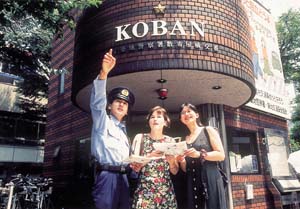

Introducing… The Kōban:

The kōban is a small neighborhood police station, two stories high at most, and accommodates 1-10 police officers. Their purpose is to provide small-scale police services such as providing directions, filing crime reports, helping with lost and found items, and offering emergency services.

There are about 6,000 kōban sprinkled around Japan. Kōban come in all sorts of shapes but they have on thing in common: They’re all small.

Not exactly the Taj Mahal are they? And that’s exactly the point! These aren’t monolithic intimidating buildings trying to subdue you with the awesome power of the Japanese police. They’re welcoming spots where you’d feel no hesitation stopping by to ask for directions to the nearest train station.

Think back to your fictional experience as an officer at the Oakland Police District headquarters, the isolation that rots your department and breeds sex scandals and racist text messages. Now imagine the OPD sprinkled around town in dozens of little kōban. A visitor stops by to ask where the California Historical Museum is, you help an old lady pick up a bag she dropped, a passerby alerts you to some minor vandalism happening nearby, a friendly merchant waves as he passes on the way to work. There’s no time to cultivate your inner vices (as there is vice in all our hearts). You’ve become as much a cheery receptionist as a police officer.

In other words, you’ve become part of the community. And it all happened because you now work in a kōban.

As we take a long hard look at what is sapping the ethics of police departments let’s not just reform rules and regulations. Let’s change the environments in which police officers operate and bring those officers out into the sunshine of community through smaller, more welcoming buildings.