Publishers Harper Wave recently sent me an advance copy of their new book, The Well-Tempered City (Amazon link) by Jonathan F.P. Rose, which discusses how cities can become sustainable and happy in the 21st century. The book covers an ambitious range of subjects from sprawl, water, and climate change, to social networks, behavior change, inequality, and happiness. No matter where you are on the change-making spectrum, you’ll find thought-provoking ideas here.

Publishers Harper Wave recently sent me an advance copy of their new book, The Well-Tempered City (Amazon link) by Jonathan F.P. Rose, which discusses how cities can become sustainable and happy in the 21st century. The book covers an ambitious range of subjects from sprawl, water, and climate change, to social networks, behavior change, inequality, and happiness. No matter where you are on the change-making spectrum, you’ll find thought-provoking ideas here.

In this post, we’ll expand upon one crucial element of the book: Integrating community participation into city planning. If cities are to make the profound changes that the 21st century will demand of them they’ll need to create new ways of engaging with communities.

Source: Angry People In Local Newspapers

Neighbors fear a library will disturb the peace? I’ve seen a lot of these kinds of conflicts recently. Earlier this year I witnessed a gymnasium full of horrified neighbors howling over a proposal to pedestrianize a street in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood. Then a similar crowd packed City Hall several months later to protest removing parking in the Parkside neighborhood across town to make safety improvements for people walking and taking transit.

One might well not condone the behavior at such public meetings and one might easily disagree with protester’s viewpoints, but it’s hard to deny that there’s a psychological need here that’s not being met. As Jonathan Rose explains in The Well-Tempered City, the tools currently in use for planning cities developed in the 20th century are now outmoded. The current citizen engagement process makes people feel like an afterthought, a process that only exacerbates their fears and entrenches their original perspectives around an idea.

James Rojas. Source: Rail LA.

Urban planner James Rojas is smart, softly-spoken, and likeable, the kind of guy you’d go frisbee golfing with. We met a couple of years ago when I’d ruffled some neighbors’ feathers by proposing the pedestrianization of a local commercial street. James taught me a valuable lesson: The way you engage a person with an issue profoundly influences their take on that issue.

James has a simple and powerful exercise to demonstrate this. A pile of knick-knacks is dumped on a table…

And participants are asked to build their favorite childhood memory…

|

Then, people get into groups and build their dream neighborhood…

|

It’s a lot of fun. You’ll see me in one of the photos above, having a great time, working with colleagues to move a community garden here and there to find the perfect location. The exercise is both playful and meaningful and children are as welcome as adults. People forget “the issues” and find common ground, rediscovering their deeper needs and what really makes a place special.

In all his years leading this exercise, James says that nobody has ever built parking lots and highways – or indeed any kind of special provision for automobiles – in their dream neighborhood. Stimulated by their childhood memories, people of all ages and backgrounds create dense, walkable places with public spaces, trees, and gardens. This happens every time.

And yet, what happens when, instead of using their creative brains to build their dream neighborhood, people are asked the simple question: What do you want to do about parking in your neighborhood? Unsurprisingly, people usually want to keep the parking.

So the way people engage with a question greatly influences the answer they give. Perhaps this is why local governments and universities looking to improve cities and campuses in meaningful ways are increasingly inviting James to lead these exercises. The results are compiled into a “values report”, summarizing the common elements of participants’ ideas.

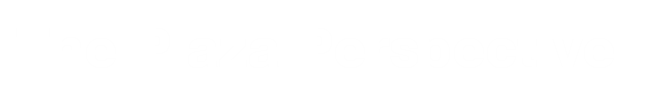

In 1997, a large project in Utah embraced a similar approach. Envision Utah, discussed in The Well-Tempered City, was an initiative to address the rapid unchecked sprawl of Salt Lake City’s suburbs. Elected officials, developers, environmentalists, business leaders, and residents were brought together to create a single vision of what they wanted this growth to look like.

During two years, over two hundred workshops were conducted. In the workshops, participants placed on a map squares representing different kinds of development, such as town houses, shopping centers, and apartment buildings. At first, participants replicated the lower-density developments they already knew. But when the facilitators pointed out that this clashed with previously-stated desires to preserve Utah’s unique nature, participants started to instead create dense, mixed-use developments. Although the project’s results weren’t legally binding, its outcomes greatly affected future development with dense building and light rail construction coming soon after.

Envision Utah succeeded because of three factors. Firstly, participants were educated about the factors to consider – air quality, land use, energy use, housing costs, and so on – in their deliberations and how their decisions would affect those factors. Secondly, a wide range and number of people were included, not just the loudest voices who typically dominate community meetings. Thirdly, like with James Rojas’s exercises, participants engaged with their hands, helping them to see the issues in a fresh light.

Increasingly, the pace of change to address 21st century challenges are being met at the city, not the national, level, especially in large countries like the US. But local governments rarely act quickly without a mandate from the people. A departure from the 20th century’s top-down projects with tokenistic citizen engagement at the end, hands on engagement methods like those of James Rojas and Envision Utah can deliver a clear message to governments to step up and create bold, positive changes.

No matter how they get around on a daily basis, everybody ultimately wants walkable, sustainable cities. It just depends on how they’re asked.