“The city is an invention to maximize exchange”

– David Engwicht

Art Kane’s classic “A Great Day in Harlem” (1958), a photo of 57 noticeable jazz musicians, is an iconic picture of community. People love to look closely at the photo and figure out the names of the different musicians.

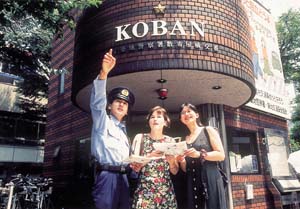

Why was the photo taken here, in this exact spot in Harlem? Exploring this question leads us into the heart of the connection between happy people and the built environment. And we’ll start here, in a very different place far away in San Francisco…

This is a typical San Francisco residential street in the west-side Sunset neighborhood, away from the photogenic sights on the tourist trail. There’s not a lot of exchange going on here, few people on the street, neighbors are generally strangers to each other. As a place to maximize exchange it’s a failure.

The common response to the phenomenon of isolated neighbors is “That’s just how people are around here, it’s their personality.” But could the built environment be playing a bigger role in this isolation than we might think?

The two main components of the built environment are streets and buildings. In a previous article, we discussed the connection between what is usually a street’s most important characteristic, its width, and human behavior. The big takeaway is that the narrower the street the more human-oriented and inviting it will be.

Today, let’s focus on the built environment’s other main element – building design – and its relationship with human connectedness. This is no trivial matter. Studies show that people living in isolating buildings are more likely to get ill, suffer from psychological issues, and be unhappy.

I’ve had an inkling of this firsthand. Having rung hundreds of doorbells as a community organizer and public space advocate, I’ve seen many times how even small differences in buildings lead to noticeable changes in behavior.

For instance, below are four types of buildings from my own neighborhood in San Francisco. I’ve ascribed each type a “sociability rating”, as defined by how likely those buildings’ residents are to respond to a ring of the doorbell. This is an inexact, subjective rating but gives a rough indication of the connection between building design and sociability.

1. Large apartment building

Units per front door: 20+

Entrance features: Gate with intercom system to contact apartments, shaded hallway beyond, ground level garage parking

Sociability rating: Very low

It’s hard to get hold of anyone in this building. Many people share the entrance, the hallway is dark and unattractive. These factors means nobody feels this area is theirs and they stay away from it. Doorbells are answered through an intercom system; residents cannot see visitors, blocking out important visual information that would make social contact more likely.

2. Small apartment building

Units per front door: 2

Entrance features: Gate with two doorbells, dark passage beyond

Sociability rating: Low

Residents often respond to the doorbell by shouting down the stairs “Who is it?” and then turning down any subsequent contact. They often don’t come to the door; the dark passageway would make the experience unpleasant if they did. However, residents have less distance to walk to the door than in the large apartment building and so are more likely to come down.

3. Single family home above garage

Units per front door: 1

Entrance features: Front door at the top of 7 steps

Sociability rating: Moderate

Residents live right behind the door, making it easy to respond to a doorbell. Features on some single-family houses, such as door and living room windows and peepholes, allow cautious residents to inspect visitors before opening the door.

4. Ground floor apartment

Units per front door: 1

Entrance features: Front door at street level

Sociability rating: Moderate to good

Living at ground level encourages residents to enter and leave the house more regularly. This particular unit also has no garage; residents will walk at least a small distance to get home (even if coming by bicycle, although the distance would be very short) and engage with neighbors. Residents are thus regularly encouraged to be sociable and are more likely to answer the door.

The lessons from these four buildings are clear: The fewer the number of residences per front door, the more inviting and attractive the entrance, and the closer to the ground people live, the more sociable they’re likely to be.

Given how significantly building design impacts social connectedness, it’s staggering that such considerations seem to be mostly ignored in today’s architecture, as evidenced by the large apartment buildings, such as the planned Coloradan project above next to Denver’s Union Station, popping up in cities everywhere. This is a profound betrayal of the public interest by the governments who allow such things to happen.

This new era of mega-buildings will have enormous implications for people’s well-being and happiness, considerations that are being ignored in the rush for Affordable Housing Now and short term corporate profits. If my neighborhood’s 20-unit 3 story apartment building is isolating, what about 100 units rising to 15 stories or more?

Social cohesiveness affects human beings to such a degree that I argue sociable environments should be defined as a human right, enshrined in building codes and zoning. That doesn’t mean everyone wants regular piñata parties outside their house; people have different social needs and preferences, of course. But it does mean that a broad range of social needs should be catered for in building design.

At the same time, many cities’ housing supplies are being outstripped by demand, housing costs are rising. So, yes, we do need more density. Is it possible to have both density and sociability? Denver’s Coloradan designers seem to be suggesting no. But there is ample evidence to the contrary…

This street in old town Corfu, Greece, explored in a previous article, saves the wasted space of wide auto-oriented streets and applies it instead to more building space, up to 4 stories tall. It is possible to infill existing auto-streets with buildings and transform them into a street like this Corfu one.

These row houses in Brighton, England, achieve density with modest size and by being located on a narrow pedestrian-only lane. If they were a story or two taller, they’d achieve even greater density. The front yards are around 10 feet deep, the ideal size, according to architect Jan Gehl, for encouraging residents to spend time there and see neighbors in the process.

These modestly-sized, tightly-packed row houses in Baltimore, Maryland, feature porches for sociability.

This historical photo shows the classic Harlem residential front stoop (left), commonly used for socializing and sitting. Buildings rise to four stories or more. Nearby shops also generate liveliness.

And that brings us back to…

…that great day in Harlem. Now we see why this location was chosen for this iconic photo. This community of musicians stands in an environment whose design encourages community. The famous sittable front stoops, the residential density, the ground level windows, this is a place that connects people.

When everybody lives in a sociable environment it’ll indeed be a great day.