Of all the unfounded myths that have wrecked our cities over the past 100 years, one stands among the giants. It’s the belief that widening roads eases congestion.

You’ve probably heard people repeat this myth over the years – your in-laws, your neighbors, and perhaps even your mayor. Indeed, recently I personally witnessed the mayors of both Austin and San Francisco, under pressure from congestion-addled residents, say exactly this.

They’re all wrong. We’ve had the evidence for a century and cities have proceeded as if they didn’t know. In the process, much that’s good about cities – their charm, strong communities, convenience, safety, economic stability – has been eroded. It would be no exaggeration to say that much of what separates great and poor cities depends on how they’ve handled congestion.

What follows is the evidence for why road-widening doesn’t work as a congestion-reliever, what road-widening actually achieves, and how congestion should really be addressed. Read it, forward it, and don’t let anybody get away with pushing road widening as a congestion solution.

Congestion sucks but not as much as you might think

Congestion is hell. According to a Hewlett-Packard study, cited in the 2013 book Happy City, people snarled in traffic suffer worse stress than fighter pilots and riot police on the job. (Just don’t take that as a recommendation to become a fighter pilot or a riot cop to avoid your commute.)

We all hate congestion. But how much of a problem is it objectively? Not as much as you might think…

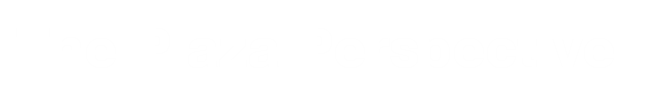

To many, congestion is one of society’s great evils. This is not the case. Even the upper estimates of congestion costs show them to be minor compared to vehicle ownership, parking costs, and air pollution impacts. Congestion isn’t a major problem and certainly shouldn’t be addressed ahead of other more damaging costs. In fact, congestion tends to increase in cities with higher GDP per capita. It’s actually a sign of success!

Widening roads only worsens congestion

For many people, including state highway department employees (aka foxes guarding the sheep), road widening is the magic pill to ease congestion. In fact, widening roads to reduce congestion is worse than doing nothing.

The Katy Freeway, Houston. Credit: Chron.

One might assume that a wider road allows traffic to flow more smoothly by allocating the same number of vehicles more space. This argument contains a fatal flaw: When roads get wider more people start driving, a phenomenon known as “induced demand”. People drive when they used to bike, walk, or take public transit; they move farther away from their jobs in town and drive farther to get there; they drive in rush hour when they used to drive at other times; and businesses that depend more on roads will relocate to cities, bringing more truck traffic with them.

(The common claim that getting more people onto bikes or into buses will take more cars off the roads and ease congestion is also bogus. Induced demand means that for every person that switches from driving to an alternative, another driver will take their place. Certainly, alternatives to driving should be encouraged for many reasons, but congestion relief shouldn’t be one of them.)

Houston’s Katy Freeway stands as only the most extreme in a long line of road widening horror stories. In 2008 Texas pumped over $2.8 billion into widening Katy to 23 lanes, making it the world’s widest freeway. The result? From 2011-2014 the morning commute time rose by 30% and the evening commute by 55%. (And you’d never believe what’s now being proposed…)

Are the new drivers’ lives significantly better? It’s unlikely. Most of this extra traffic, because it’s of the kind that’s easily given up when congestion gets bad, is considered of marginal value. And the extra costs of collisions, vehicle ownership, air pollution, and other costs (see the chart above) eat further into the dubious benefits of all those new drivers.

Narrowing or removing roads eases congestion

If widening roads worsens congestion then is it also true that narrowing or removing roads reduces congestion? Yes. A 1998 study of 60 cases worldwide showed that when a road is closed or its capacity reduced an average of 20% of traffic disappears. The study found instances where 60% of the traffic disappeared. It isn’t displaced to other roads, it simply vanishes. We’re back to those marginal value rides again. There’s great flexibility in people’s trips and it’s relatively easy for them to avoid making the trip, change its timing, or ride another way.

This is a crucial piece of evidence to support what should be a priority for towns and cities everywhere: Creating public space – car-free and in the center of town. Even if this public space occupies former auto-oriented streets (usually the best candidates for public space), there’s unlikely to be much overflow to neighboring streets.

A beautiful place for people. Quincy Market, Boston MA. Credit: Boston Geology.

Road widening is bad economics

State departments of transportation (DOTs) – often jokingly called highway departments (which is what some of them actually used to be called) – seek out road-building projects as a way to keep their personnel in work.

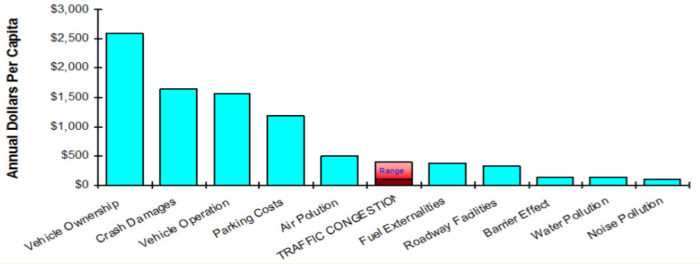

This might be good for highway builders but it’s bad for the economy overall. A 2010 study concludes that bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure creation (a drop in the bucket of all state DOT expenses) generates up to double the number of jobs compared to automobile infrastructure. For every $1,000,000 spent on gasoline only about 5 jobs are generated (and this is a generous estimate).

And the aftermath of road-widening is an even more automobile-oriented society, which weakens local economies. Most auto-related spending leaves the local economy, auto-infrastructure prevents land from generating property taxes, and tourists tend to avoid car-oriented places.

The lesson is simple: Road widening is bad economics.

How to actually move people more quickly

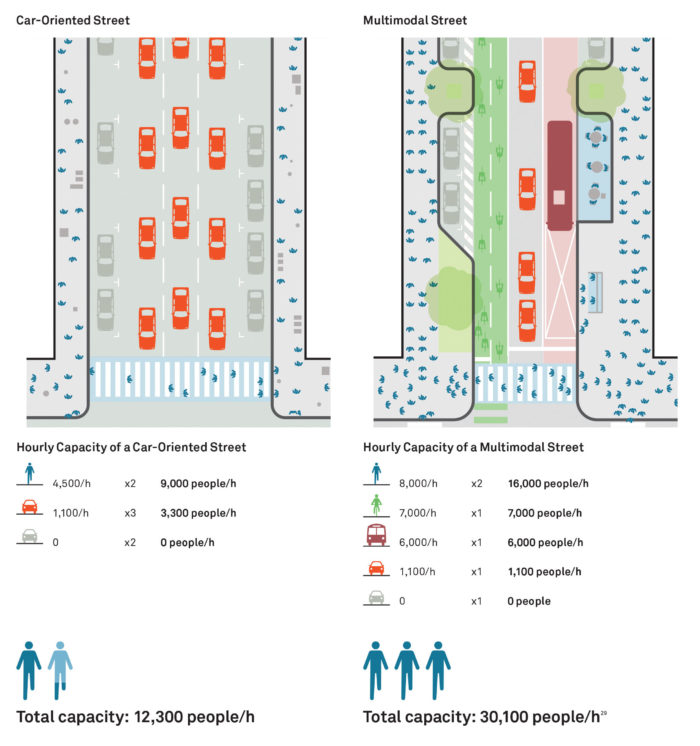

We’ve established that widening roads is not an effective way of reduce commute times. So what is? The answer is the “multimodal street”, a fancy way of saying a street designed for not only cars but for walking (sidewalks), bicycling (protected bike lanes), and public transportation (bus-only lanes).

Let’s compare the capacity of a car-oriented street with a multimodal street:

Source: NACTO Global Street Design Guide

The evidence is that streets with bike lanes, bus-only lanes, wide sidewalks, and (if they must be there) car lanes carry over twice as many people per hour and thus decrease travel times as streets designed for just cars. This is because biking, busing, and walking consume much less space per person and encourage more compact development, reducing traveling distances.

Go Sing It On The Mountain

No longer can road widening be justified as a congestion-easing tool. Road widening lengthens commutes, increases household costs, worsens pollution, harms the economy, and, let us not forget, kills and injures millions of people globally every year. Transportation departments and politicians had the evidence decades ago and many continue to ignore it to this day. We need to make them understand.

The solution to congestion is compact development and multimodal (and sometimes pedestrian-only) streets. Wherever cars come into contact with well-designed human-scaled cities there’ll always be congestion; cars are extremely inefficient uses of space, after all, and are incompatible with great places. The question is: Do we want a lot of traffic congestion or a little?

And remember: Not all types of congestion are bad…

The charts used in this article are part of Victoria Transport Policy Institute‘s Todd Litman’s excellent presentation “Economics of Highway Spending and Traffic Congestion“, a highly recommended read.